read – TOKAFI

France Jobin is not trying to understand the world – but her own place, in it.

France Jobin is a sound artist’s favourite sound artist. Minute attention to detail, a penchant for precision and an ear for beauty in unusual places have translated into a discography that may not be overly prolific, but continues to impress the true sonic connoisseurs. It is also the result of an anything but typical biography, which saw her rebelling against her classical education by performing keyboard in a blues band for many years, before discovering her affinity for the electronic medium. Despite emerging as one of the leading artists of the microsound scene of the early millennium, Jobin’s style always remained deeply personal, infused with a sense of fragility and sensitivity that resulted from an intimate relationship with her sounds and where they might lead her. After more than a decade of operating under the i8u moniker, Jobin switched to using her civilian name on the occasion of her 2012 work Valence on Richard Chartier’s LINE imprint, a decision she would stay true to for her latest full-length The Illusion of Infinitesimal. In many respects, the album marks an acme within her oeuvre, although, as she stresses, it is merely the logical result of continuing her proven style and philosophy: “I felt it important to maintain and respect in the tradition that Richard Chartier established for his label. One of consistency and uncompromising attitude towards minimalism. With The Illusion of Infinitesimal, I attempted to push further this notion of peeling away superfluous layers so that only the true essence of each sound remains.”

You once asked yourself: “Why do I love to hear classical music but loathe playing it?” I’d be curious about your answer to that question.

Perhaps, I have today come closer to an answer. I still love classical music but I think it was not the right medium through which I could communicate properly. I found that many of the emotions I felt were not being conveyed clearly through playing the piano and interpreting someone else’s works. My aim was to communicate what I felt.

You have gradually moved from your background as a classically trained pianist towards different interfaces. How content are you with these interfaces compared to the keyboard?

Moving to interfaces and electronic music as a whole really freed me. Electronic music for me flows effortlessly and is close to what I am trying to convey. I also love sound, I love the variety of sounds that exists. When I was playing keyboards or piano, I was under a traditional music sphere of time signature, keys, notes, chords, etc. It is possible to get away from those with keyboards and sound programming, but personally, I always felt restrained. I needed to unlearn all that I had learned to enable me to make experimental music. When one plays keyboards, one is playing one bar while reading the next. This implies that you know what to expect. I felt this was a hindrance for experimental music. I had to rid myself of the years of training except for one thing, the actual act of listening. Everything else had to go. I can now say that I have started incorporating elements of my old training back in my work, I have been including piano and “musical elements”, as “sounds”.

For a few years, you would be active as a performer in a blues band. What were some of the experiences that would lead you towards the discovery of ‘the room’ as part of the sonic experience?

Playing blues and touring was a great “school of sound” for me. While touring, one is often subjected to less than perfect conditions in regards to the venue, sound system etc. Jazz festivals present a different dynamic, outdoor stages, where the sound is often lost. One learns very quickly that the most important person to a musician, is the sound man and that including him equally in the process is intrinsic to the performance. Among the things I witnessed for instance, was that the good blues players would always talk about the “feel”. No matter how technical a musician, if he did not have that “feel”, the subtleties of the idiom were not assimilated in the playing. Less notes, more feel was always the aim. I realized this was my initial exposure to a minimalist approach.

Another expression often used was ” being in the pocket” or “staying in the pocket”. This one was aimed at the rhythm section – drums and bass – and the important relationship between the two. If they were in sync, anything was possible, if they were not, the whole structure fell apart.

These concepts shaped my listening experience. I listened to each instrument individually, and to all of them, as one. During that time, we would have to adjust to each room we played, the guitarist with his amp and effects, me on keyboards and again, the band as a whole. If one room had too much treble, we would have to compensate, if the stage was set in front of a huge window, we knew that meant trouble as the sound had no solid wall to bounce from. I cannot tell you how many times we walked into a room and had to adjust on the fly because of so many different elements such as what the walls or floors were made of, how high was the ceiling and so on. It became such a regular occurrence that eventually, I found myself walking into a room and within seconds, know exactly what the room would sound like. When having to do our own sound – which was often the case – I was the one designated to do so. As I gained experience, it became obvious to me that the room played an integral part of the performance.

Once I switched to experimental music, I was able to take this experience further, using the room to my advantage. I feel I can really push this notion to its fullest with the use of frequencies that “bring out” the acoustic qualities of a room and exploit them.

You took a break from music after giving birth to your two sons. What were you listening to in these ten years? Did you end your compositional activities completely or are there still some productions from this period?

I listened to all kinds of music as I always do, jazz, electronic, classical, reggae and so on. Among others, this included Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thomas Köner, Richard Chartier, Asmus Tietchens, Pan Sonic, Mika Vainio, Bach, Mozart, Gustav Mahler, King Crimson and many more … Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue was and still is a regular on my playlist.

My sons were born very close to each other, which resulted in a period of chronic lack of sleep. During those early years, I proceeded to transform my studio, learn analog gear and hardware as well as get acquainted with computer generated methods. I spent a lot of time learning computer related methods while “unlearning” my previous musical training. There are no productions from this period but rather, all this work culminated in the release of my first self titled i8u CD. Strangely though, it would take me until 2003 to take the plunge and perform strictly with a laptop.

Especially with your most recent releases, I am noticing your use of terminology from the realm of physics for track titles and to describe the music.

As my children became older and more independent, I had more time to pursue interests. Science, physics, quantum physics were natural choices as I strived to move towards a more streamlined approach to life. Quantum physics describes the nature of the universe as being much different than what we see. This is exciting to me because every field recording I make, I listen to in this way, which is also how I view life. This pursuit of knowledge in science translated to a similar path in my music and naturally influenced my approach to sound and composition. My sound processing slowly became about the peeling away of each superfluous layer, until I reached the essence of each sound, from that, it effortlessly moved to each movement within a piece and composition as a whole.

I am not so much trying to understand the world as I am trying to understand myself, in it.

If I understood correctly, you also began programming your own software tools at one point.

My stint in programming was brief and only lasted one and a half years. I took workshops for MAX/msp and managed to create one instrument that I use when I improvise with other musicians. Although I found the experience freeing and very creative, the amount of time needed for me to become proficient in programming was also time taken away from making music. I was happier programming sounds and composing.

One of the things that would become more and more apparent in your music was your move towards quiet dynamics. What happens when sound approaches the threshold of perception, do you feel?

Everything happens. It changes one’s perception, it forces one to listen more intently and by that very act, makes the listener actively involved with the work. It opens up the floodgates to the myriad of possibilities. Amplitude can change the nature of a sound completely. Low amplitude to me is a great tool, it creates magic as you listen over and over. It never is quite what you heard at first.

The dominant underlying intent throughout my work, be it albums, concerts or installations, is to make people stop, remove all distractions, and listen, simply listen.

Pierre-Alexandre Tremblay once asserted that “writing for electronics requires the same knowledge as writing for orchestra”. Is that something you can relate to?

Absolutely, in electronics, you are composing with sounds instead of instruments.

Why then, as you recently wrote in the press release to your new album, is it an ideal to detach yourself from the sounds?

Sounds to me, are like children, one cares for them, nurtures them and eventually, they detach, and only in that very delicate act of detachment, can their true essence be revealed.

What are some of the criteria that make you feel satisfied with a sound or piece?

I approach each piece with a sound that pleases me at that particular moment. The attention to details comes in the sound processing and ensuring that these sounds delicately compliment each other. Albums are great because they give me the luxury to “obsess” on a 3 second fade for a week or as long as it takes until I am satisfied. I recently had a discussion about this with Christopher Bissonnette and we both agreed that “deleting the dots” is a painstaking but satisfying exercise! I feel a sound or a piece is finished when I have managed to transpose what I hear in my head as accurately as I possibly can.

When you’re immersed in sound all day, digging deep into the details, doesn’t it become less fascinating – because you understand the way certain things work?

Au contraire, being immersed in sound all day has become exponentially more fascinating. Unlike some, who have been conditioned to tune out background noise, I get caught in endless loops of analyzing how it makes me feel, and how I can manipulate these sounds if I could capture them. Mystery will always remain a part of the process as I try to understand what is reality. As I try to interpret and recreate this reality, it is clear to me that sound is the foundation of my own.

How do you see the balance between the emotional and the intellectual in your compositions?

I think this may come from my own attempts to find the same balance in my life. The emotional and intellectual balance is an inclusive one for me, I don’t see how one can exist without the other, within us. Sounds can evoke both emotions as well as intellectual appreciation. I believe that by presenting sounds that are physical puts the listener in a state of receptivity, when that state of mind is achieved, it becomes easier to introduce the more intellectual sounds, which may not be so pleasing at first. It’s a matter of context, and how things are presented.

What is your concept of beauty?

For me, it’s one where artists or musicians are able to communicate their unique identity. If they have found that identity and refined it, it will be clearly communicated through their work.

France Jobin interview by Tobias Fischer

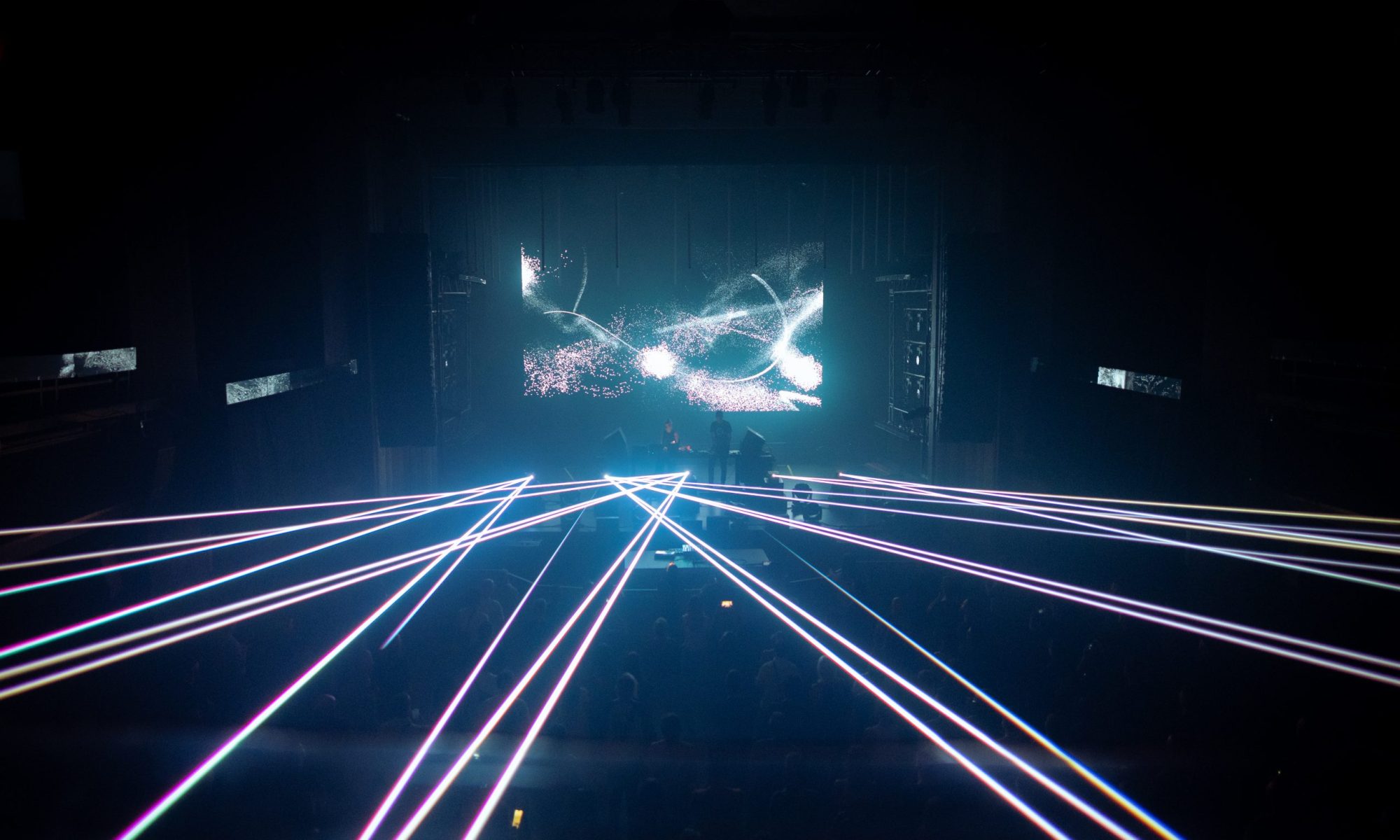

France Jobin photos by Sandor Dobos